Her

Honour Judge Melissa Clarke:

INTRODUCTION

1.

This case involves design

rights in baby baths. Baby bath design has become significantly more

sophisticated since I last purchased one about 13 years ago, which was little

more than an elongated bucket. They are now available in a myriad of sizes,

shapes and colours with numerous features such as collapsibility for storage,

detachable cups to pour water, integral drains etc. Of particular importance to

this case is the development of a common feature which appears to be

colloquially known in the field as a “bum bump”. This is a feature which is

intended to stop a slippery wet baby from sliding down the bath and underneath

the surface of the water. It is generally (but not always) a moulded ‘lift’ at

the bottom of the baby bath, so that the baby’s bottom sits in the space to the

rear of it and the baby’s legs sit over or around it, hence preventing

slippage. It has the added benefit of providing support to free the carer’s

hands to wash the baby.

2.

The Claimant (“Shnuggle”) is a small company based in

Northern Ireland, which designs, manufactures and sells baby products. The

First Defendant (“ Munchkin”)

Munchkin”) is a

large company based in the US, which does the same. The Second Defendant (“Lindam”) is an indirect subsidiary of

is a

large company based in the US, which does the same. The Second Defendant (“Lindam”) is an indirect subsidiary of

Munchkin.

Munchkin. It is based in the UK and distributes

It is based in the UK and distributes  Munchkin’s

Munchkin’s products here. Mr

Michael Hicks appears for Shnuggle and Ms Lindsay Lane, Queen’s Counsel,

appears for

products here. Mr

Michael Hicks appears for Shnuggle and Ms Lindsay Lane, Queen’s Counsel,

appears for  Munchkin

Munchkin and Lindam.

and Lindam.

Shnuggle

and the Shnuggle Mk1 and Shnuggle Mk 2 baths

3.

In 2012 and 2013 Shnuggle (through

its director and product designer Adam Murphy) designed and developed for

production a baby bath made from expanded polypropylene foam, which it first

sold on the market in January 2014. It sold about 700 units in total: half in

the UK and half to retailers in Spain and Poland. I will refer to this baby

bath as the Shnuggle Mk 1.

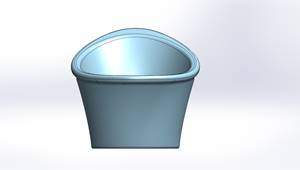

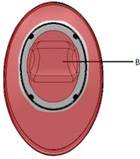

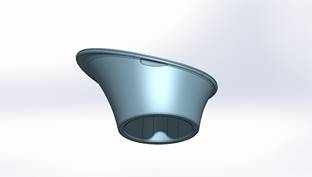

Fig 1a, 1b, and 1c: Shnuggle Mk 1

4.

Shnuggle was not satisfied

with the production quality of Shnuggle Mk 1 and so it developed that design

further between August and December 2014, producing a version made from

thinner, injection moulded polypropylene. This first sold on the market in the

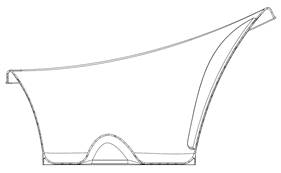

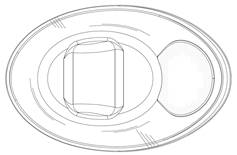

UK in early 2015. I will refer to this baby bath as the Shnuggle Mk 2.

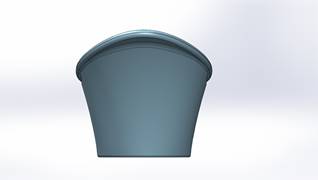

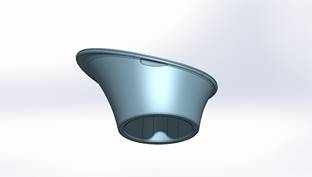

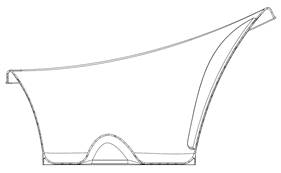

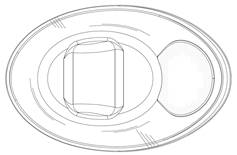

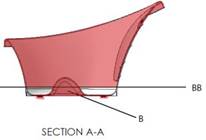

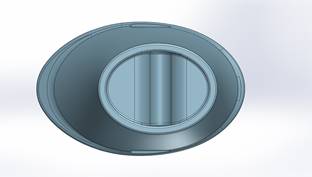

Fig 2a, 2b: Shnuggle Mk 2

5.

The Shnuggle Mk 2 has

achieved significant commercial success in the UK, Europe, North America, Asia

and Australia, selling online and through major retailers. These include, in

the UK, John Lewis, Argos, Mothercare and Mamas and Papas.

6.

Shnuggle own two

registered Community designs with which this claim is concerned (the “RCDs”):

i)

No. 002224196-001 (“RCD-196”) filed on 20 April 2013 in

respect of the Shnuggle Mk 1 (see Annex

1 to this judgment);

ii)

No.

002616763-0001 (“RCD-763”) filed on

20 January 2015 in respect of the Shnuggle Mk2 (see Annex 2 to this judgment).

7.

Shnuggle also claims UK

unregistered design rights under section 213 of the Copyright Designs and Patents

Acts 1988 (“CDPA”) in respect of 6

designs (“UDRs”) which relate to certain

parts of the Shnuggle Mk 1 and Shnuggle Mk 2 baby baths (“Shnuggle Designs”). The Shnuggle Designs are identified in the

Particulars of Claim at paragraphs 12(1) to (6) and at Annex 5 thereto. Some

(but not all) views of the Shnuggle Designs have been set out, conveniently, in

a single table in the Claimant’s skeleton argument, and I reproduce that at Annex 3 to this judgment.

Munchkin

Munchkin and the Sit & Soak bath

and the Sit & Soak bath

8.

Mr Quinn Biesinger, senior

product designer of  Munchkin,

Munchkin, designed a baby bath for

designed a baby bath for  Munchkin

Munchkin in October and

November 2017. This was first sold on the market in the UK in January 2019

under the name “Sit & Soak”. The Sit & Soak is sold online and through

retailers including Argos.

in October and

November 2017. This was first sold on the market in the UK in January 2019

under the name “Sit & Soak”. The Sit & Soak is sold online and through

retailers including Argos.  Munchkin

Munchkin accepts: (i) that there is no evidence that

Mr Biesinger saw or had access to the Shnuggle Mk 1; and (ii) that Mr Biesinger

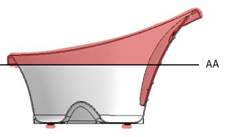

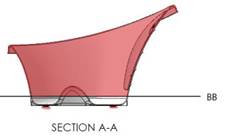

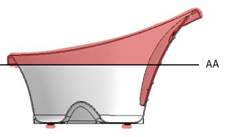

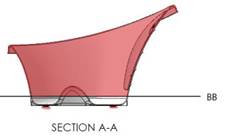

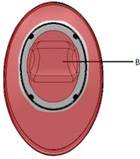

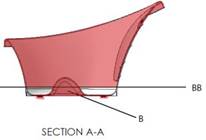

had a sample of the Shnuggle Mk 2, which was a point of reference and an

inspiration for the design of the Sit & Soak. Indeed, an internal email of

26 October 2017 briefing Mr Biesinger during the design process describes his

objective as “aiming for a Shnuggle

inspired design with some added

accepts: (i) that there is no evidence that

Mr Biesinger saw or had access to the Shnuggle Mk 1; and (ii) that Mr Biesinger

had a sample of the Shnuggle Mk 2, which was a point of reference and an

inspiration for the design of the Sit & Soak. Indeed, an internal email of

26 October 2017 briefing Mr Biesinger during the design process describes his

objective as “aiming for a Shnuggle

inspired design with some added  Munchkin

Munchkin flair and features”. After a

meeting on 1 November 2017 in which Mr Biesinger had presented some designs, he

was instructed to “Head more toward

Shnuggle based on Amazon reviews”.

flair and features”. After a

meeting on 1 November 2017 in which Mr Biesinger had presented some designs, he

was instructed to “Head more toward

Shnuggle based on Amazon reviews”.

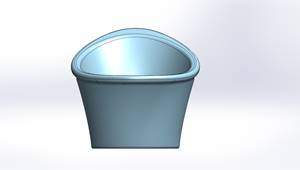

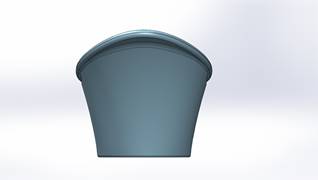

Fig 3a, 3b, 3c: Sit & Soak

9.

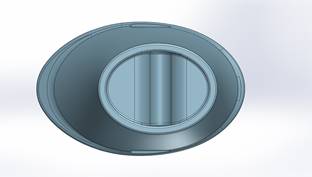

Fig. 4a, 4b and 4c below show

the Shnuggle Mk 1 (left), Shnuggle Mk 2 (centre) and Sit & Soak (right) side

by side from the top, side and underneath.

The parties’ cases

10.

Shnuggle claims that the

Sit & Soak infringes both the UDRs and the RCDs.

11.

In respect of the UDRs,  Munchkin

Munchkin and Lindam dispute subsistence of the rights, deny copying and deny infringement.

and Lindam dispute subsistence of the rights, deny copying and deny infringement.

12.

Munchkin

Munchkin and Lindam rely

on the following pleaded prior art as commonplace designs:

and Lindam rely

on the following pleaded prior art as commonplace designs:

i)

The Tippitoes mini bath (“Tippitoes”):

Figs. 5a, 5b and 5c: Tippitoes

ii)

The Mothercare slipper bath (“Mothercare slipper”):

Figs 6a, 6b, 6c: Mothercare slipper

iii)

The Amalfi slipper bath (“Amalfi”), which is not a baby bath:

Figs. 7a, 7b, 7c: Amalfi

iv)

The Mebby Cocoon portable

baby bath (“Mebby Cocoon”):

Figs. 8a, 8b, 8c

v)

The Shnuggle Mk 1 (see above).

13.

In respect of the RCDs,

Munchkin

Munchkin and Lindam deny infringement and by their counterclaim challenge their

validity on the basis of prior art. However this was narrowed at trial as the

challenge to the validity of RCD-196 was not pursued. Accordingly only the

validity of RCD-763 remains in issue.

and Lindam deny infringement and by their counterclaim challenge their

validity on the basis of prior art. However this was narrowed at trial as the

challenge to the validity of RCD-196 was not pursued. Accordingly only the

validity of RCD-763 remains in issue.

14.

It is not disputed that if

the Sit & Soak bath infringes either the UDRs or the RCDs, Lindam is also

liable, as both Lindam and  Munchkin

Munchkin accept joint responsibility for the sale of

the Sit & Soak in the UK.

accept joint responsibility for the sale of

the Sit & Soak in the UK.

THE ISSUES

15.

His Honour Judge Hacon

made a directions order on 26 March 2019 which limited the issues for

determination at trial. Those are reproduced below, amended slightly to reflect

the position at trial:

Registered Designs

i)

Whether [RCD-763 is] valid;

ii)

Whether the Sit & Soak

bath is an infringement of the RCDs;

Unregistered

Designs

iii)

Whether design right is

capable of subsisting in the Shnuggle Designs as being designs for the whole or

part of an article;

iv)

Whether the Shnuggle Designs

are original;

v)

Whether the Shnuggle

Designs are commonplace;

vi)

Whether the Sit & Soak

is an article which has been made by copying the Shnuggle Designs;

vii)

Whether the Sit & Soak

is an article which has been made to produce articles exactly or substantially

to each of the Shnuggle Designs.

The

Evidence

16.

As is usual in IPEC, HHJ

Hacon directed that the statements of case stand as the evidence in chief. He

further directed that the parties be permitted witness statements of fact in

respect of issue 1 (validity of the RCDs), 4 (originality), 5 (commonplace) and

6 (copying).

17.

He directed expert

evidence, including from Mr Murphy as an in-house expert, on issue 1 (validity

of the RCDs), issue 2 (infringement of the RCDs), issue 5 (commonplace), issue

6 (copying) and issue 7 (exactly or substantially), with the evidence on issues

1, 2 and 7 being limited to comparative drawings and explanations.

18.

In addition, the parties

have prepared a chart in the form recommended as useful by HHJ Hacon in Action Storage Systems Limited v G-Force

Europe.com Limited [2016] EWHC 3151 to assist the court in considering

individual features of the designs.

19.

Shnuggle relies on a

single witness: Mr Adam Murphy as both a witness of fact and an expert witness.

He filed a witness statement dated 14 June 2019 and an expert report dated 2

August 2019 and was cross-examined and re-examined.

20.

Munchkin

Munchkin and Lindam rely

on the following witnesses:

and Lindam rely

on the following witnesses:

i)

Mr Quinn Biesinger, the

lead designer of the Sit & Soak, as a witness of fact. He filed a witness

statement dated 13 June 2019 upon which he was cross-examined and re-examined.

ii)

Mr Nicholas Trumbo as a

witness of fact. He filed a witness statement dated 13 June 2019 which, subject

to some agreed redactions, is not disputed. Accordingly he did not attend

trial.

iii)

Mr Michael Corcoran,

industrial designer, as an expert witness for the Defendants. He filed a report

dated 2 August

2019 and was cross-examined and

re-examined.

21.

I found Mr Murphy and Mr Biesinger

to be good, straightforward witnesses of fact. I am satisfied that each of them

endeavoured to assist the court with truthful evidence to the best of their

ability, recollection and belief. Mr Murphy did, as Ms Lane submits, have a

difficult job in being both witness of fact and expert but I consider that he

did so carefully and avoided too much elision of those roles, although

inevitably there was some. Ms Lane in particular says that there were concessions

he should have made as an expert which he did not make, probably because of the

close identification he had with the Shnuggle baths as their designer. I accept

that, but they were few.

22.

I found Mr Corcoran to be

a good expert of assistance to the court.

23.

I will consider the claims

in respect of the RCDs first before moving onto the UDRs.

THE

REGISTERED DESIGN CLAIMS

Legislation

24.

Council Regulation 6/2002/EC of 12 December 2001 on

Community designs (“the Regulation”)

applies. The relevant Articles include the following:

“Article 4

Requirements

for Protection

1. A design shall be protected by a Community design

to the extent that it is new and has individual character.

…

Article 5

Novelty

1. A design shall be considered to be new if no

identical design has been made available to the public:

...

(b) in the case of a registered Community design,

before the date of filing of the application for registration of the design for

which protection is claimed, or, if priority is claimed, the date of priority.

2. Designs shall be deemed to be identical if their

features differ only in immaterial details.

Article 6

Individual

character

1. A design shall be considered to have individual

character if the overall impression it produces on the informed user differs

from the overall impression produced on such a user by any design which has

been made available to the public:

...

(b) in the case of a registered Community design,

before the date of filing the application for registration or, if a priority is

claimed, the date of priority.

2. In assessing individual character, the degree of

freedom of the designer in developing the design shall be taken into

consideration.

Article 10

Scope of

Protection

1. The scope of the protection conferred by a

Community design shall include any design which does not produce on the

informed user a different overall impression.

2. In assessing the scope of protection, the degree of

freedom of the designer in developing his design shall be taken into

consideration.”

25.

Jacob LJ in Dyson Ltd v Vax Ltd [2012] FSR 4 at [8]

and [9], emphasising a passage from his judgment in Procter & Gamble v Reckitt Benckiser [2008] ECDR 3 at [3] and

[4] said “The most important things are

the registered design, the accused object and the prior art, and the most

important thing about each of these is what they look like”. The Supreme

Court in Magmatic approved this pithy

summary of registered design law.

Discussion

of legal principles

New

26.

‘Immaterial details’ means

‘only minor and trivial in nature, not affecting overall appearance’. This is

an objective test. The design must be considered as a whole. It will be new if

some part of it differs from any earlier design in some material respect, even

if some or all of the design features, if considered individually, would not

be.

Individual

Character

27.

Recital 14 to the

Regulation provides some guidance on the meaning of ‘individual character’:

“The assessment as to whether a design has individual

character should be based on whether the overall impression produced on an

informed user viewing the design clearly differs from that produced on him by

the existing design corpus, taking into consideration the nature of the product

to which the design is applied or in which it is incorporated, and in

particular the industrial sector to which it belongs and the degree of freedom

of the designer in developing the design.”

28.

Designs within the

existing design corpus must be considered individually, and not by combining

features of some designs with those of others.

Informed

User

29.

What is the nature of the

informed user? He or she is notional and a construct. The Court of Appeal

approved the description of HHJ Birss QC (as he then was) sitting as a High

Court Judge at [33] and [34] of Samsung

Electronics (UK) Ltd v Apple Inc. [2012] EWHC 1882 (Pat), [2013] ECDR 1 in

the appeal from that judgment Samsung

Electronics (UK) Ltd v Apple Inc. [2012] EWCA Civ 1339, [2013] FSR 9:

“[33] The designs are assessed from

the perspective of the informed user. The identity and attributes of the

informed user have been discussed by the Court of Justice of the European Union

in PepsiCo v Grupo Promer (C-281/10P)

[2012] RSR 5 at paragraphs 53 to 59 and also in Grupo Promer v OHIM [2010] ECDR 7, (in the General Court from which

PepsiCo was an appeal) and in Shenzen Taiden v OHIM, case T-153/08, 22

June 2010, BAILII: [2010] EUECJ T-153/08.

[34] Samsung submitted that the

following summary characterises the informed user. I accept it and have added

cross-references to the cases mentioned:

He (or she) is a user of the product in

which the design is intended to be incorporated, not a designer, technical

expert, manufacturer or seller (PepsiCo paragraph

54 referring to Grupo Promer

paragraph 62);

However, unlike the average consumer of

trade mark law, he is particularly observant (PepsiCo paragraph 53);

He has knowledge of the design corpus and

of the design features normally included in the designs existing in the sector

concerned (PepsiCo paragraph 59 and

also paragraph 54 referring to Grupo

Promer paragraph 62);

He is interested in the products concerned

and shows a relatively high degree of attention when he uses them (PepsiCo paragraph 59);

He conducts a direct comparison of the

designs in issue unless there are specific circumstances or the devices have

certain characteristics which make it impractical or uncommon to do so (PepsiCo paragraph 55).

[35]

I would add that the informed user neither (a) merely perceives the designs as

a whole and does not analyse details, nor (b) observes in detail minimal differences

which may exist (PepsiCo paragraph

59).”

Technical function

exception

30.

Registered design

protection will not subsist in ‘features of appearance of a product which are

solely dictated by its technical function’ (Article 8(1) of the Regulation).

31.

If all of the features of

appearance of the product are solely dictated by its technical function, then

the registration will be invalid (per the UK Board of Appeal decision in Lindner Recyclingtech

v Franssons Verkstader

[2010] ECDR 1) which is not binding upon, but which has been approved by, English

courts: see Arnold J in Dyson v Vax,

approved by the Court of Appeal on appeal and Birss J in Sealed Air v Sharp Interpack. This is not such a case. However, where

only one or more features of appearance of a product are solely dictated by its

technical function, but others are not, considerations arise about scope of

protection and the design freedom of the designer.

Degree

of Design Freedom

32.

The court must take the degree

of freedom of the designer in developing the design into consideration both in

assessing ‘individual character’ (Article 6(2) of the Regulation) and in

assessing the scope of protection (Article 10 of the Regulation). It is

important because similarities between products which are attributable to

design constraints will be given little significance in the comparison of the

overall impressions they produce. Where there is a high level of design

freedom, attention is likely to be focussed on those parts where there is a

greater potential for variability.

33.

His Honour Judge Hacon sitting

as a Judge of the High Court in Cantel

Medical (UK) Ltd v ARC Medical Design Ltd [2018] EWHC 345 (Pat) discussed

the designer’s degree of design freedom, setting out the key points to

consider:

i)

The constraints imposed by

the technical function of the product or the statutory requirements;

ii)

Similarities between the

designs of corresponding parts of two products which are attributable to design

constraints will be given little significance in the comparison of the overall

impressions they produce;

iii)

Where there are at least

some elements in respect of which the designer had a high level of design

freedom, attention is likely to be focused on those parts with their greater

potential for variability. Similarities cannot be explained away be design

restraints and will tend towards the view that overall impressions do not

differ, whereas differences will lead towards the opposite conclusion;

iv)

Finally, when comparing

the design in question to the design corpus, HHJ Hacon in Cantel explains at [169] that:

a)

A design which is markedly

different will confer a greater scope of protection;

b)

Little or no weight should

be given to common features.

Design Representation

34.

An issue in this case is

the impact of the colour and contrast shown on a registered design to the scope

of protection. That is because when a registered design comes before the court

which is to determine the scope of protection, the question is a matter of the

proper interpretation of the relevant registration, and the images included in

that representation.

35.

In PMS International Group Plc v Magmatic Limited [2016] UKSC 12, Lord

Neuberger (with whom all others agreed) said at [32]:

“It is for an

applicant to make clear what is included and what is excluded in a registered

design and he has wide freedom as to the means he uses. It is not the task of

the court to advise the applicant how it is to be done.”

36.

He further quoted with

approval from the writings of Dr Martin Schlotelburg, of the EUIPO design

department:

“…the

selection of the means for representing a design is equivalent to the drafting

of the claims in a patent: including features means claiming them.”

37.

In summary, it is up to

the applicant for a registered design right to decide what to apply for (e.g.

the design for the whole article or just part, and if so what part(s)), what

features to include in the design application and what to leave out, and how to

represent them. As  Munchkin

Munchkin submits, and as I accept, per Magmatic on appeal, where a design is registered in colour and/or

contrast, then that must be taken into account when considering infringement,

and the use of colour and/or contrast will serve to limit the scope of the

registered design.

submits, and as I accept, per Magmatic on appeal, where a design is registered in colour and/or

contrast, then that must be taken into account when considering infringement,

and the use of colour and/or contrast will serve to limit the scope of the

registered design.

Assessment

38.

I will deal with whether

the Sit & Soak infringes RCD-196 before going on to consider whether

RCD-763 is valid and, if so, whether the Sit & Soak infringes it.

Who

is the informed user?

39.

I consider that the market/industrial

sector is the general market for baby baths, rather than a wider market for

baths generally (which would include adult or specialist baths). It is common

ground that the informed user is an interested and observant adult user of baby

baths who may be a parent, carer, or relative of the baby who is to use it. He

has the characteristics identified by HHJ Birss in Samsung v Apple set out above.

What

is the design corpus?

40.

It is common ground that

there is a wide and varied design corpus in the general market for baby baths

of which the informed user would be aware, and I have been provided with

physical examples of many of them. They include the Tippitoes, Mothercare

slipper, Mebby Cocoon and Shnuggle Mk 1 which are part of the prior art I have

identified for the UDR claim, but also a great number of others, including: a

“traditional” Mothercare bath; the Tummy Tub; the Boon Naked which is a

collapsible bath; the Boon Soak; the Nuby which is almost identical to the

Tippitoes; and the John Lewis Value bath which is another ‘slipper’ type bath

similar to the Mothercare, with a higher back than front, albeit the latter has

a more modern aesthetic.

Is

the RCD-196 new and does it have individual character?

41.

It is Shnuggle’s case that

the RCD-196 is a significant design departure from existing baby baths, which

were either of a more traditional type requiring the baby to recline back

considerably while being bathed, or of ‘bucket’ type baby baths like the Tummy

Tub and Mebby Cocoon.  Munchkin

Munchkin accepts that there is no evidence in the design

corpus of any identical design which had been made available to the public in

the UK at the time the RCD-196 was designed, and nor is there any baby bath

whose features differ only in immaterial details.

accepts that there is no evidence in the design

corpus of any identical design which had been made available to the public in

the UK at the time the RCD-196 was designed, and nor is there any baby bath

whose features differ only in immaterial details.

42.

Munchkin

Munchkin submits that

RCD-196 is an intermediate type bath, suitable for older babies than newborns,

which allows them both to be supported in a more upright position at 3-5 months

or so, and also to sit by themselves from 5 or 6 months old. Mr Murphy accepted

all of those points in cross-examination. However

submits that

RCD-196 is an intermediate type bath, suitable for older babies than newborns,

which allows them both to be supported in a more upright position at 3-5 months

or so, and also to sit by themselves from 5 or 6 months old. Mr Murphy accepted

all of those points in cross-examination. However  Munchkin

Munchkin submits that the

Tippitoes is a similar intermediate-type bath with similar features, and of

similar size to the Shnuggle Mk1. It points to an email written by Mr Murphy to

his wife while he was designing the Shnuggle Mk1 attaching a screenshot of the

Tippitoes and entitled “A similar

bath!!!” I accept that there are similarities in what the Tippitoes is

trying to achieve in terms of aiming at a similar age-range of baby, producing

support in the form of an angled back in a more upright position and with a bum

bump. However design right does not protect ideas. The way in which the

Tippitoes and the RCD-196 achieve those aims is visually extremely different in

my judgment, giving rise to a significantly different design.

submits that the

Tippitoes is a similar intermediate-type bath with similar features, and of

similar size to the Shnuggle Mk1. It points to an email written by Mr Murphy to

his wife while he was designing the Shnuggle Mk1 attaching a screenshot of the

Tippitoes and entitled “A similar

bath!!!” I accept that there are similarities in what the Tippitoes is

trying to achieve in terms of aiming at a similar age-range of baby, producing

support in the form of an angled back in a more upright position and with a bum

bump. However design right does not protect ideas. The way in which the

Tippitoes and the RCD-196 achieve those aims is visually extremely different in

my judgment, giving rise to a significantly different design.

43.

I am satisfied that

RCD-196 is new and has individual character.

What

are the technical constraints and the degree of freedom of the designer?

44.

I must consider what

features of the design of a baby bath are solely dictated by technical constraints

or other design constraints . In doing so I am

considering designs for the industrial sector I have identified, i.e. the

general baby bath market. Accordingly the design constraints include

constraints of volume manufacture and sale. I am not concerned with

hand-hammered, bespoke copper baby baths, which is a different market.

45.

Shnuggle submits that the

only real technical constraints on the designer of a baby bath are that the

bath must hold water and be sufficiently large to take a baby. I accept those

are two constraints, but I do not accept those are the only ones.

46.

Munchkin

Munchkin submits that the

designer of a baby bath is subject to a number of design constraints which

limit the scope of protection, and which I set out below with my comments:

submits that the

designer of a baby bath is subject to a number of design constraints which

limit the scope of protection, and which I set out below with my comments:

i)

The baby

will be within a range of proportions (depending on its age). I agree that it is a design

constraint that a baby bath must fit babies of different sizes and shapes

within the age range that it is designed for, and that a baby’s size will

increase over the time during which the baby bath will likely be used;

ii)

The baby will not (at least

initially) be able to support itself or its head and limbs. This seems to me to relate to the

baby and is not a constraint on the design of the bath. Although I accept that

a younger baby will require some support when using a baby bath, that support

could be provided entirely by the baby’s carer, as is the case when one bathes

a baby in a sink. Any requirement for the baby bath itself to provide partial

or full support may be a design objective, but in my judgment it is not a

design constraint.

iii)

The baby bath needs to be small

enough to fit in a sink. I

do not accept that as a design constraint, although it may be a design

objective. There are many volume-manufactured baby baths which do not fit into

a sink. In addition it raises further questions about the size and shape of the

sink it must fit in, sinks also being subject to very wide variation (as

accepted by Mr Corcoran in cross-examination);

iv)

The baby bath needs to be light

enough to be portable.

I accept that as a design constraint;

v)

The baby bath needs to be stable

with the water and baby in.

I accept that as a design constraint as a matter of both safety and

practicality;

vi)

There needs to be enough space to

wash the baby. I

accept that as a design constraint;

vii)

The baby bath needs to be suitable

for volume manufacturing at a relatively low price point. I agree it needs to be suitable for

volume manufacturing and sale but this relates to the sector, and is not a

design constraint. I do not know what “relatively low” means in this context.

Relative to what? I accept there is a range of acceptable prices, as did the

experts in cross-examination. In fact nothing turns on it; and

viii)

The baby bath needs to be capable of

being easily stacked during transport, storage and retail. I accept this is a design

constraint related to the sector, which is general baby baths for volume

manufacturing and sale.

47.

Despite

these constraints, I am satisfied there is still a large degree of design

freedom in the size (within a range), shape and overall appearance of a baby

bath. This can be seen in the surprisingly wide range of baby bath designs contained

in the design corpus.

What

features are common in the design corpus?

48.

Munchkin

Munchkin submits that the

following features, identified by Mr Corcoran, are common in the design corpus:

submits that the

following features, identified by Mr Corcoran, are common in the design corpus:

i)

slipper

baby baths (where the back is higher than the front) (see Mothercare slipper,

John Lewis value);

ii)

having

the back at an angle to support the baby’s head;

iii)

a

bum bump;

iv)

a

pad at the baby’s head or back for comfort;

v)

a

base and sides;

vi)

narrower

sides and a wider top; and

vii)

a

skirt or flange around the base.

49.

Mr Murphy accepted these

as common in cross-examination. Miss Lane also suggested, and he accepted, that

an ellipse or oval shape for the base and top was common. I accept all of these,

and that little or no weight should be given to common features. She further suggested that a concave exterior

curve from the higher at the top to lower at the bottom of the bath was common

and he accepted it existed in the design corpus, but I don’t consider, looking

at the design corpus, that it is common. I can see it in the Mebby Cocoon,

which itself is a relatively unusual bath, but the vast majority of the design

corpus have a convex exterior curve or are straight-sided. I do not find that

to be common.

Scope of design

ascertainable from the registration

50.

The scope of design

ascertainable from the registration is viewed through the eyes of the informed

user. How would he interpret the registration, which in this case is a series

of CAD renderings without commentary? In particular, what is the significance

of the colour of the renderings?

51.

Shnuggle submits that the

colour of RCD-196 would be interpreted by the informed user to be off-white in

colour, or perhaps a bluey-grey (but in any event monochrome), and he or she would

interpret the colour in the rendered drawings as having no purpose save to

indicate, in the tonal differences of the rendering, the shape of the design. Accordingly

Shnuggle submits that the scope of design should not be limited to the colour

blue and it is for shape only.

52.

I accept  Munchkin’s

Munchkin’s submission that as a matter of fact, RCD-196 is registered in blue, whether

that was Shnuggle’s intention or not. I cannot accept that the informed user

would perceive the renderings either as off-white, or as a bluey-grey monotone

intended to be any colour or none. Mr Murphy very fairly accepted in

cross-examination that they were blue. If Shnuggle had wanted to register only

the shape of the bath, instead of positively choosing the colour blue, it could

have provided a line drawing (as it did for RCD-763) or rendered it in

monochrome shades of grey. In my judgment that colour choice limits the scope

of protection, per Magmatic.

submission that as a matter of fact, RCD-196 is registered in blue, whether

that was Shnuggle’s intention or not. I cannot accept that the informed user

would perceive the renderings either as off-white, or as a bluey-grey monotone

intended to be any colour or none. Mr Murphy very fairly accepted in

cross-examination that they were blue. If Shnuggle had wanted to register only

the shape of the bath, instead of positively choosing the colour blue, it could

have provided a line drawing (as it did for RCD-763) or rendered it in

monochrome shades of grey. In my judgment that colour choice limits the scope

of protection, per Magmatic.

What

overall impression does the design, prior art and accused product give?

53.

Munchkin

Munchkin submits that the

most notable features of the RCD-196 when compared to the prior art are:

submits that the

most notable features of the RCD-196 when compared to the prior art are:

i)

the

perfect oval shape formed by the top and back of the bath;

ii)

the

prominent flat rim;

iii)

the

handles on the middle of the sides;

iv)

the

absence of a back pad;

v)

the

colour blue; and

vi)

the particular shape of the bump.

I agree with

that list, save that I consider the fact that the bum bump is a hump which goes

from side to side at the base of the bath is notable by the informed user,

rather than any specific dimensions or cross-section of it. I would also add

that I consider the way in which the body of the bath flares out from the oval

base to the oval top to be a notable feature. None of these, save the last

which I have added, are present in the Sit & Soak.

54.

Shnuggle submits that the

similarities between the RCD-196 and the Sit & Soak include:

i)

The generally oval cross-sections,

and the proportions of the ovals in RCD-196 (i.e. length and width) are very

similar. I do not

consider that the informed user will be assessing the similarity of the two

designs by reference to cross-sections or measurements, although I accept that

he or she will notice whether proportions are similar or dissimilar. I consider

that the informed user will consider that the Sit & Soak is of generally

similar proportions, but with an elongated back.

ii)

All the horizontal cross-sections

are oval. I accept

that the informed user will note the oval base, the oval pedestal and the

generally oval tops of RCD-196 and the Sit & Soak but again I do not

consider he or she will perceive them in terms of cross-sections.

iii)

The very similar ‘bum bump’ in terms

of both height and position. I

accept the height and position are similar but I consider the informed user

will perceive the shape of the bum bumps as differences.

iv)

The way in

which the upper edge of the baths start relatively horizontally and then curve

upwards, leading to a higher back than front. This is a description of a slipper bath which I have

found to be common.

v)

The similar rolled edge effect. I disagree. RCD-196 does not have a

rolled edge but a flat solid rim.

55.

Munchkin

Munchkin submits that the differences are:

submits that the differences are:

i)

RCD-196 is thick walled, whereas the

Sit & Soak is thin walled. That means that the rolled edge effect, while

similar, is created differently.

I disagree. I accept Shnuggle’s submission that the thickness of the walls of

RCD-196 are not easy to perceive from the design, and certainly not in the way

that it is easy to perceive in the Shnuggle Mk1. Accordingly I do not consider

that the informed user would perceive this as a significant difference,

although they might extrapolate from the thick edge that there is some

difference in thickness.

ii)

The Sit & Soak is slightly

longer (4.8% at the bottom, 7.2% at the top). I consider that the informed user has no reason to

measure these baths and will perceive them as very similar in proportions at

the bottom, but will perceive that the Sit & Soak is longer at the top

because of the elongated back in which the handle is placed.

iii)

The Sit & Soak ‘bum bump’ is

slightly different at the corners, but the cross-section is almost identical. I do not consider that the informed

user will be assessing what the two bumps might look like in cross-section. As

I have already indicated, I think the informed user will perceive that the bump

is similar in terms of placement and height, but will consider the shape of the

bump to be quite different.

iv)

The back of the Sit & Soak extends

upwards more than in RCD-196. I

agree.

v)

While the upper edge curves upwards

in both when viewed from the side, the Sit & Soak curve is slightly

different. I

consider the informed user will perceive Sit & Soak to be quite different

in this aspect.

vi)

The Sit & Soak has a padded back

that has been stuck on after manufacture of the main bath. I agree that the padded back is a

difference but I do not know that the informed user will perceive how it has

been manufactured.

vii)

The base of the Sit & Soak has a

flange and the underside is consequently different. I do not consider that the informed

user will pay very much attention to the flange or the underside, save for the

feet.

viii)

The Sit & Soak has a plug. I am satisfied that the informed

user will perceive this difference.

Discussion and decision

56.

In my judgment the main visual

similarities between the RCD-196 and the Sit & Soak are around the shape

and proportions of the body or pedestal of both, and in particular the profile

of the body of the baths as they rise and flare out from base, below the rim. The shape and size of the body of

the bath are subject to some design constraints, but that elegant externally

concave rise from an oval base which the RCD-196 and Sit & Soak share is

not seen elsewhere in the design corpus before the RCD-196. The closest is the

Mebby Cocoon which has a rounder base, smaller proportions and does not flare

out to the same extent, although it does display external concavity. I agree

that the higher back than the front in both the RCD-196 and Sit & Soak is

visually similar, but I consider that this is common in the slipper-type baths

in the design corpus.

57.

The

main differences that I consider would be identified by the informed user, are

the following:

i)

The

Sit & Soak does not show the perfect oval shape of the top of the RCD-196.

Rather, it has been pulled out and extended at the back in a sort of teardrop

shape, so that the overall shape of the bath is like a Chinese soup-spoon,

rather than the purer flared-oval shape of the RCD-196. I consider that the

informed user would give this significant weight as it produces a significantly

different visual impression, and the shape of the top of the Sit & Soak is

not seen in the design corpus.

ii)

The

thin, floating edge of the Sit & Soak, which is pulled out from the sides

and front of the bath but not the rear elongated back/handle, is quite

different to the thick, seemingly solid rim around the whole of the top of RCD-196.

Again, I consider that the informed user would give this significant weight as

the visual impression that each create is quite different – airy and floating

in the Sit & Soak and solid in the RCD-196.

iii)

The

treatment of the handles. RCD-196 has small, quite unobtrusive handles at the

side under the thick rim, whereas the Sit & Soak has no handles at the

sides but instead a hole punched in the elongated back to serve as a handle.

Again, I consider that the informed user would give this significant weight as

the back and hole together produces a significantly different visual

impression, both as a handle but also as a semi-circular hole. I consider that

the informed user, when considering this hole, will understand this hole has

practical utility as a means of storing the bath on a hook.

iv)

The

back pad. RCD-196 has no back pad, whereas the Sit & Soak has a back pad

which is a distinctive shape and extends the full length of the back and around

the handle/hole. Although I have found

that a comfort pad at the back or head is a common feature, there is some

design freedom in placement, size, and shape of that pad and the choices made

in the distinctive Sit & Soak back pad are not seen in the design corpus

and provide a noticeable visual impression. Accordingly I consider that the

informed user will give this significant weight.

v)

Presence

of a drain in the Sit & Soak in a bold contrast colour. There is none in

RCD-196 and this will be perceived as a significant visual difference.

vi)

Bum

bump. This is an “island” type of bump in the Sit & Soak and a hump from

wall to wall of RCD-196. I accept it is a point of difference as well as a

point of similarity. Although the fact of the ‘bum’ bump is similar, and it is

placed a similar distance from the back of the tub where the baby sits, in my

judgment the informed user will perceive and give some weight to the different

visual impressions given by the different shapes of the bump, because he will

note that the baby’s legs can rest either side of the Sit & Soak ‘island’,

which it cannot in the RCD-196. I do not place that weight very high, but it provides

some weight.

vii)

The

colour. I have found that RCD-196 is limited in scope to the colour blue. The

Sit & Soak is white with blue contrasts in the back pad, drain, feet and

small non-slip details on the base.

viii)

Other

differences include the flange around the base of the Sit & Soak and the

additional non-slip pad on the base of the Slip & Soak which do not appear

in RCD-196, but these are very minor differences. I consider the informed user will

notice the non-slip pad, but give it very little weight. I doubt he will notice

the flange at all.

ix)

I

do not consider that the informed user will give any material weight to the

differences of the underside of the base, (including the differences in the

construction of the flange) which are not visible in use, save that the

contrasting blue feet of the Slip & Soak are noticeable enough to perhaps

be noticed, particularly while the bath is overturned to be emptied or dried,

or hung up on the back of a door as the hole in the handle enables it to be.

58.

Of

course it is easier to perceive similarities and differences than to describe

them in words. What matters is the overall

visual impression arising from a side-by-side comparison of RCD-196 and the Sit

& Soak. In my judgment if the informed user stands

back and looks at the two together, directly comparing them with everything in

mind that I have mentioned including the prior art, the Sit & Soak will

produce a different overall visual impression in his or her mind. I would also

have reached this conclusion even if I had found that RCD-196 was not limited

in scope to the colour blue. The key reasons are in the Sit & Soak’s unusual

teardrop shape compared to RCD-196’s oval, the extended, lengthened back to

form a handle with a hole punched out of it, the distinctive shape and

contrasting colour of the back pad extending up into and to the top of the

handle, and the difference between the solid, flat, rim around the whole of the

RCD-196 and the delicate floating edge of the front and sides only of the Sit

& Soak.

59.

For those reasons I find

that the Sit & Soak does not infringe RCD-196

Validity of RCD-763

60.

It

is common ground that design corpus for RCD-763 includes the Shnuggle Mk1 and

RCD-196.  Munchkin

Munchkin submits that RCD-763

is very similar to RCD-196 except:

submits that RCD-763

is very similar to RCD-196 except:

i)

It

is not limited by colour, being a line drawing;

ii)

It

has no handles at the side

iii)

It

has a back pad

iv)

It

has a different ‘island’ shaped bump.

61.

I

have found that my decision in relation to RCD-196 would have been the same

even if it was not limited by colour, so that does not take us any further. I

accept those other differences exist. To those I add from Shnuggle’s

submissions: (v) RCD-763 has a flange and a consequently different underside of

the base from RCD-196, and (vi) that the rim, while visually similarly thick

from above, can be perceived to be a thinner rolled rather than solid edge.

62.

Mr

Hicks also submits for Shnuggle that another difference between RCD-196 and

RCD-763 is that the former is thick walled and the latter is thin-walled. I

accept that is a difference between the Shnuggle Mk1 and the RCD-763 but I

again find it difficult to perceive the thickness of the walls from the RCD-196

design when compared to the RCD-763 design.

63.

In

terms of whether a design is new, this is measured against identical designs which

have been made available to the public. I do not understand Miss Lane’s

submissions for  Munchkin

Munchkin to be that the RCD-763 is identical to the Shnuggle Mk

1 save for features which differ only in immaterial details, so she sensibly

does not make the argument that RCD-763 is invalid as it is not new. Rather she

submits that each of the other differences identified above are trivial from

the perspective of the overall impression of the informed user, such that the

RCD-763 does not make an overall impression which differs from that produced by

RCD-196 or the Shnuggle Mk1 (both being prior disclosure), and so it is invalid

for lack of individual character.

to be that the RCD-763 is identical to the Shnuggle Mk

1 save for features which differ only in immaterial details, so she sensibly

does not make the argument that RCD-763 is invalid as it is not new. Rather she

submits that each of the other differences identified above are trivial from

the perspective of the overall impression of the informed user, such that the

RCD-763 does not make an overall impression which differs from that produced by

RCD-196 or the Shnuggle Mk1 (both being prior disclosure), and so it is invalid

for lack of individual character.

64.

Mr

Hicks submits that the differences identified are all present in the Sit &

Soak and therefore amount to similarities rather than differences between the

Sit & Soak and RCD-763. Where I have rejected his primary case of

infringement of RCD-196, he submits that these differences are visually important,

and give individual character, so RCD-763 is valid over RCD-196. However he

goes onto accept that if RCD-763 is valid, it will have a relatively narrow

scope of protection because of the presence of RCD-196 and Shnuggle Mk 1 in the

design corpus. Nonetheless he submits that the Sit & Soak will produce a

very similar overall impression to the RCD-763 and accordingly I should find

that it is infringed.

65.

I

am with  Munchkin.

Munchkin. The handles at the side of the RCD-196 are extremely

unobtrusive and their absence in RCD-763 makes little difference to the visual

impression. The back pad is different, but it is also common both in fact and

in the manner of its execution, so the informed user will give it no weight.

The flange is common and of no interest to the informed user in my judgment. The

differences to the underside I consider that the informed user will accord no

weight. The rim is a rolled edge but the visual impression is of a similar flat

wide rim to that of RCD-196 around the entirety of the top of the bath. The

island shaped bump is slightly different to the RCD-196 in shape and placement

but I do not consider it to be different enough to give, together with the

absence of handles, a clearly different overall visual impression, particularly

including the level of design freedom that I have found is accorded to a baby

bath designer. Accordingly I find that RCD-763

is invalid for lack of individual character.

The handles at the side of the RCD-196 are extremely

unobtrusive and their absence in RCD-763 makes little difference to the visual

impression. The back pad is different, but it is also common both in fact and

in the manner of its execution, so the informed user will give it no weight.

The flange is common and of no interest to the informed user in my judgment. The

differences to the underside I consider that the informed user will accord no

weight. The rim is a rolled edge but the visual impression is of a similar flat

wide rim to that of RCD-196 around the entirety of the top of the bath. The

island shaped bump is slightly different to the RCD-196 in shape and placement

but I do not consider it to be different enough to give, together with the

absence of handles, a clearly different overall visual impression, particularly

including the level of design freedom that I have found is accorded to a baby

bath designer. Accordingly I find that RCD-763

is invalid for lack of individual character.

66.

If

I am wrong about that, and it does produce a sufficiently different overall

visual impression to RCD-196 to be valid, I consider that the Sit & Soak

nonetheless will give a different visual impression to the informed user to RCD-763,

for the same reasons I gave in respect of RCD-196, and so I would find it not

to infringe RCD-763.

THE UNREGISTERED DESIGN CLAIMS

Legislation

67.

Section 213 of the Copyright, Patents and Designs Act

1988 was amended by the Intellectual Property Act 2014. It provides, so far as

is relevant, as follows:

“(1) Design right is a property right which subsists

in accordance with this Part in an original design.

(2) In this Part ‘design’ means the design of the

shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of the whole or part of

an article.

(3) Design right does not subsist in—

(a) a method or principle of construction,

(b) features of shape or configuration of an article

which—

(i) enable the article to be connected to, or placed

in, around or against, another article so that either article may perform its

function, or

(ii) are dependent upon the appearance of another

article of which the article is intended by the designer to form an integral

part, or

(c) surface decoration.

(4) A design is not ‘original’ for the purposes of

this Part if it is commonplace in the design field at the time of its

creation.”

68.

Section

226(1) CDPA provides that a person who is entitled to unregistered design right

has the exclusive right to reproduce the design for commercial purposes by

making articles to that design or by making a document recording the design.

69.

Section

226(3) provides:

“Reproduction

of a design by making articles to the design means copying the design so as to

produce articles exactly or substantially to that design”.

Discussion

of legal principles

70.

There

are three controversial areas of law between the parties on the legal

principles:

i)

What

is a “part of an article” following the amendment to section 213(2) CDPA by

section 1(1) of the Intellectual Property Act 2014 (“IPA 2014”)?

ii)

Is

it necessary that a “part of an article” be separately created for the purposes

of section 213(2)?

iii)

What copyright

threshold should be applied in assessing originality?

What

is part of an article?

71.

Section

1(1) of the Intellectual Property Act 2014 removed three words from section

213(2) CDPA, which previously read:

“In this Part

‘design’ means the design of any aspect

of the shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of the whole

or part of an article” (my emphasis).

72.

Section

213 has been the subject of considerable judicial criticism since it was

introduced in the 1988 Act. In Dyson Ltd

v Qualtex (UK) Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 166; [2006] RPC 31, Jacobs LJ (with

whom Lloyd LJ and Tuckey LJ agreed) said in respect of the unamended Section

213 at [14]:

“It has the merit of being short. It has no

other. Jonathan Parker J considerably

understated the position, when he said, “regrettably, the drafting of section

213 leaves much to be desired” (Mark

Wilkinson Furniture v Woodcraft Designs [1997] FSR 63 at p.27). It is not

just a question of drafting (though words and phrases such as “commonplace”

“dependent”, “aspect of shape or configuration of part of an article” and

“design field in question” are full of uncertainty in themselves and pose near

impossible factual questions). The problem is deeper: neither the language used

nor the context of the legislation give any clear idea what was intended. Time

and again one struggles but fails to ascertain a precise meaning, a meaning

which men of business can reasonably use to guide their conduct. The amount of

textbook writing and conjecture as to the meaning is a testament to its

obscurity. We just have to do the best we can, trying to arrive at “an

interpretation which the reasonable reader would give to the statute read

against its background” per Lord Hoffmann in R (Wilkinson) v IRC [2005] UKHL 30, [2006] 1 All ER 529 at [18].

The absence of any clear policy, as to where the line of compromise was

intended to run, means that brightline rules cannot

be deduced”.

73.

It

is Shnuggle’s case that that the Shnuggle Designs are each a design of “part of an article”.  Munchkin

Munchkin pleads

that each of the Shnuggle Designs is a design of an “aspect of the shape or configuration… of the whole or part of an

article”, and not “part of an

article”, and so, following the amendment of section 213 to excise

‘aspects’, are unprotectable. Miss Lane goes further and submits for

pleads

that each of the Shnuggle Designs is a design of an “aspect of the shape or configuration… of the whole or part of an

article”, and not “part of an

article”, and so, following the amendment of section 213 to excise

‘aspects’, are unprotectable. Miss Lane goes further and submits for  Munchkin

Munchkin that there is no rationale or reason for Shnuggle to seek to exclude particular

aspects of the designs of the Shnuggle Mk1 and Shnuggle Mk2 in the Shnuggle

Designs, and so it can be inferred that the reason it seeks to do so is because

the Sit & Soak does not reproduce those features and because the Sit &

Soak does not substantially reproduce the overall designs for the whole of the

articles. Miss Lane argues that the purpose of the amendment to section 213(1)

was to prevent claimants from chopping products up into little pieces in order

to try and emphasise those pieces which are similar or the same in the designs

and ignore the bits which are different.

that there is no rationale or reason for Shnuggle to seek to exclude particular

aspects of the designs of the Shnuggle Mk1 and Shnuggle Mk2 in the Shnuggle

Designs, and so it can be inferred that the reason it seeks to do so is because

the Sit & Soak does not reproduce those features and because the Sit &

Soak does not substantially reproduce the overall designs for the whole of the

articles. Miss Lane argues that the purpose of the amendment to section 213(1)

was to prevent claimants from chopping products up into little pieces in order

to try and emphasise those pieces which are similar or the same in the designs

and ignore the bits which are different.

74.

I

do not accept this submission. It is specifically provided in section 213(2)

that the right can subsist in relation to the shape or configuration of the

whole or part of an article. As Lewison J put it at [27] of Virgin Atlantic Airways Ltd v Premium

Aircraft Interiors Group Ltd and Anor [2009] EWHC 26(Pat), “One of the real difficulties of section 213

is that the claimant may select a part of the article and claim design right

for that part only. The courts have recognised this possibility since early

days of design right”. He cites Ocular

Sciences Ltd v Aspect Vision Care Ltd [1997] RPC 289 and A. Fulton Co Ltd v Totes Isotoner

(UK) Ltd [2004] RPC 16.

75.

Laddie

J (as he then was) giving the judgment of the court in Ocular Sciences said at page 422:

“The proprietor can choose to assert design

right in the whole or any part of his product. If the right is said to reside

in the design of a teapot, this can mean that it resides in design of the whole

pot, or in a part such as the spout, the handle or the lid, or, indeed, in a

part of the lid. This means that the proprietor can trim his design right claim

to most closely match what he believes the defendant to have taken. The

defendant will not know in what the alleged monopoly resides until the letter

before action or, more usually, the service of the statement of claim”.

76.

Jacob

LJ refined this a bit in Fulton v Totes,

saying at [34]:

I do not

fully go along with Laddie J.’s suggestion that what the proprietor can do is

to “trim his design right claim”. It is not really a question of “trimming” –

it is just identifying the part of his overall design which he claims has been

taken exactly or substantially. And although Laddie J. was right in saying that

the defendant will not know in what the alleged

(my emphasis) monopoly resides until the letter before action or claim form,

that does not mean the defendant does not know where he stands before then. The

man who copies a part of an article exactly or substantially, will know what he

has taken. It is true that it will be for the designer to formulate his claim

properly in any proceedings, but the subsistence of his rights does not depend

on how he frames his claim”.

77.

Miss

Lane for the Defendants submits that these pre-amendment cases are of little

assistance to the interpretation of section 213(2) as amended, but I do not accept

this submission. These authorities provide useful guidance as to the meaning of

“part” of a design and I consider that they remain useful guidance.

78.

To

the extent that Miss Lane submits that the guidance in those authorities refers

only to an ‘aspect’ of a design, I also do not accept that is so. Fulton

v Totes was an appeal against a finding that a separate design right

subsisted in a “cut off” design, i.e. where part of the article was removed

from consideration and design right asserted in what remained. The appeal was

on the basis that it was a creation of an artificial new design right in the

guise of selecting part of the actual design. At [13] to [28] Jacobs LJ

dismissed this argument, stating that unregistered design right subsisted in

“any aspect of the shape and configuration of part of an article” (original emphasis), emphasising ‘part’ not

‘aspect’. That he was considering ‘part’ is also clear in [32] in which he

explained that the appellant’s argument overlooked, inter alia, the must fit must match exceptions in section 213(3),

which he described as:

“features

which, if present, will be parts of an article (e.g. the fitting bits of a new

design of electrical plug). Plainly it was thought that unless they were

excluded they would be covered by the word “part” in the definition of design.

And it is to be noted that …the must fit/must match exception is put in at the

stage of designing design right, not at the stage of providing exceptions to

infringement”.

Is

it necessary for a part of an article to be separately created?

79.

The

Defendants submit that the following principles can be discerned from the case

of Neptune (Europe) Limited v DeVol

Kitchens Limited [2017] EWHC 2172 (Pat):

i)

To

be a part, as opposed to an aspect, something should be created separately and

not simply be a disembodied feature of a whole.

ii)

A

combination of parts created separately may nevertheless amount to an aspect.

iii)

A

part can be identified by the exclusion of other parts created separately.

80.

In

Neptune, the late Henry Carr J

considered the effect of the deletion of the words “any aspect of” from section

213(2). The case was about designs for kitchen furniture, and an issue was

whether some features which formed part of the Neptune kitchen units (but were not

seen in the alleged infringing units) could be excluded from consideration of

the design alleged to be infringed. Those features included cock-beading and moulding

on the doors of Neptune’s units. One issue in the case was whether Neptune in

seeking to exclude those features was seeking to rely upon “parts” rather than

“aspects” of the designs. Henry Carr J determined the point as follows at [44]

(original emphasis):

“This raises

the subtle question of the difference between “parts” and “aspects” of a design. In my view, aspects of a design include

disembodied features which are merely recognisable or discernible, whereas

parts of a design are concrete parts, which can be identified as such.

Returning to the example of Laddie J in Ocular Sciences, aspects of the design of a teapot could include the

combination of the end portion of the spout and the top portion of the lid,

which are disembodied from each other and from the spout and lid. They are not

parts of the design.

In my

judgment, none of the features which Neptune seeks to exclude, nor the

remainder of the designs after such exclusion, are properly characterised as

aspects of the designs. For example, the cock-beading and moulding are concrete

parts of the designs, which are created separately and then applied to the

Chichester cabinets.

The position

would be different if Neptune was seeking to rely upon the combination of key

features as a design, but that is not its case. I accept Neptune’s argument

that, since the statute permits designs for parts of articles, it makes no

difference whether those parts are identified by their presence, or by the

absence of excluded parts. In my judgment, Neptune is entitled to rely upon the

entirety of the designs in question, without the features which

it seeks to exclude.”

81.

In

reaching that conclusion, Henry Carr J considered a number of authorities

including Dyson v Qualtex and DKH Retail.

82.

In

Dyson v Qualtex Jacob LJ discussed

what was the threshold or limit of an ‘aspect’ of a design. He said at [22]:

“... UDR can subsist in the “design of any aspect of

the shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of the whole or part

of an article.” This is extremely wide—it means that a particular article may

and generally will embody a multitude of “designs”—as many “aspects” of the

whole or part of the article as can be. What was the point of defining “design”

in this way I do not know. The same approach is not adopted for ordinary

copyright where the work is treated as a whole. But even with this wide

definition, there is a limit: there must be an “aspect” of at least a part of

the article. What are the limits of that? I put it this way in A. Fulton Co Ltd v Totes Isotoner

(UK) Ltd [2004] R.P.C. 16; [2003] EWHCA [sic] Civ 1514 at [31]:

“The notion conveyed by ‘aspect’ in the composite phrase ... is ‘discernible’

or ‘recognisable’”.

83.

Of course, requiring an

aspect merely to be “discernible” or “recognisable” is a very low threshold

which is hardly a threshold at all. If something is neither discernible nor

recognisable it is difficult to see how one could even characterise it as a

design, let alone how one could copy an indiscernible or unrecognisable aspect,

or establish it had been copied. As Jacobs LJ himself accepted in Fulton v Totes at [23], a design right “…is limited to preventing copying and

copyists must know what they are copying”.

84.

This

perhaps is at the heart of the contradiction HHJ Hacon identified in DKH Retail Ltd v H Young Operations Ltd [2014] EWHC 4034 (IPEC), [2015] FSR 21 when considering the effect of the excision

of the words “any aspect of” from section 213(3) at [10] – [18]. HHJ Hacon asked how, if “any aspect

of” was a threshold which narrowed the definition of a claim per Dyson v Qualtex, the removal of those

words would not have the effect of widening the definition, or alternatively

and at the very least, have no effect. However he was satisfied that was not

the effect, as paragraph 10 of the Explanatory Notes to the Intellectual

Property Act 2014 makes explicit that the intention of Parliament in making

this change was to narrow the definition further:

“Subsection (1) limits the protection for trivial

features of designs, by making sure that protection does not extend to ‘any

aspect’ of the shape or configuration of the whole or part of an article. It is

expected that this will reduce the tendency to overstate the breadth of

unregistered design right and the uncertainty this creates, particularly in

relation to actions before courts.”

85.

He concluded that one possible interpretation of the

effect of the amendment is:

“that

it no longer permits a claim to unregistered design right to extend to designs

other than those specifically embodied in all or part of the claimant’s

article, i.e. no more UK unregistered design rights in abstract designs...”.

86.

In

reaching his conclusions in Neptune,

Henry Carr J endorsed HHJ Hacon’s view that an effect of the amendment was that

there were to be no more unregistered design rights in disembodied or abstract

designs.

87.

I

do not accept the Defendant’s submission that ‘part’ of an article must be

separately created, in order be protected under section 213, for the following

reasons:

88.

First,

I do not understand Henry Carr J to be using “a concrete part which can be identified as such” to mean that a

part is only a part if it is separately created, or a separate component;

rather I understand him to be explaining in use of the word “concrete” that a

part must be an actual part of the

article, or as HHJ Hacon put it in DKH

Retail, “specifically embodied in”

all or part of the article, and not merely abstract.

89.

Second,

there is nothing in the statute which suggests that separate creation is a

requirement and I accept Mr Hicks’ submission that it would lead to absurdities

if an identifiable part of one article (say, a handle on the lid of a teapot) was

a ‘part’ for the purposes of section 213(2) because it had been created

separately (and then applied to the lid), and the same identifiable part of an

otherwise identical article was not, because it was manufactured in one piece (with

the lid). I do not understand Henry Carr J to be saying that it is necessary

for a part to be created separately but rather that if, as in the facts of Neptune, part of an article is separately

created, that may assist the court in identifying it as a part.

90.

Third,

there is nothing in the pre-amendment authorities put before me which supports

the contention that a “part” of an article must be separately created, although

the need for a part to be identifiable is well established, see for example Ocular Sciences at [34]. Mr Hicks for

Shnuggle submits that such an interpretation is contrary to Fulton v Totes (CA) at [28] and [29] and Virgin Atlantic v Premium at [31]. I

accept that submission.

91.

It

seems to me that now that the words ‘any aspect of’ have been excised from

section 213(2) there is no longer any practical utility to considering the

question “What is the difference between a ‘part’ and an ‘aspect’ of an

article?”. The relevant question should now be only “Is this a design for ‘part’

of an article?” We are still in the situation identified by Jacob LJ of having

to do the best we can with section 213(2) to arrive at the interpretation which

the reasonable reader would give the statute, read against its background.

However we are in a better position than was Jacob LJ at the time of Dyson v Qualtex, because we no longer

have “an absence of any clear policy, as

to where the line of compromise was intended to run”; we have the paragraph

10 of the Explanatory Notes to the Intellectual Property Act 2014 which tells us that the changes to section

213(2) were intended to narrow the definition by excluding trivial features

from protection.

92.

Accordingly

I consider that a part of an article for section 213(2) is an actual, but not

abstract part which can be identified as such and which is not a trivial

feature. Whether or not it is a trivial feature is a matter of fact which will

need to be assessed in the context of the article as a whole.

What

is the correct test for originality?

93.

Section 213(1) CDPA protects “original designs”.

Subject to the question of whether a design is commonplace, Shnuggle submits that

originality is to be assessed in the same way as originality in the context of

copyright law under the old UK common law copyright test of labour, skill and

effort. Per Russell-Clarke & Howe on

Industrial Designs, 9th Ed. at [4-046] to [4-047]: “original means that the design has been

originated by the author, in the sense of not having been copied from a previous

design, and the author has expended sufficient skill or labour on its creation

that it can fairly be counted as original”. HHJ Hacon applied the old UK copyright test in

DKH Retail at [19], referencing Magmatic at first instance at [84].

94.

The Defendants submit that it is not correct to say

the old UK copyright test applies, and draw the court’s attention to (i) Arnold

J’s application of the new test from Infopaq

(work comprising the expression of the author’s own intellectual creation) in Whitby Specialist Vehicles Ltd v Yorkshire

Specialist Vehicles Ltd [2014] EWHC 4242, and (ii) HHJ Hacon more recently

acknowledging in Action Storage Systems

Ltd v G-Force Europe.com Ltd [2016] EWHC 3151 that it was arguable that the

Infopaq test applied [22], but

finding that it made no difference on the facts of that case. I add to those

submissions that it appears from the reference in paragraph [51] of Neptune to “the copying of ideas expressed in a design which… involved original

design skill and labour and/or are the expression of the intellectual creation

of their author” that there was no concern before Henry Carr J about which

test should be used, probably because it too did not matter in the

circumstances of that case. There are a number of authorities which have conflated

the tests or declined to specify which test was being used on the grounds that

it didn’t matter.

95.

Miss Lane for the Defendants submits that in Action Storage HHJ Hacon held that the

new test raised the hurdle. I don’t believe that is controversial. As Mr Hicks

acknowledged in closing, and as I find, it also does not make any difference in

this case, in my judgment, so I will decline to determine the point, and leave

it for a case where it does make a difference.

Submissions and Discussion

Designs for the shape or

configuration of any part of an article?

96.

The first question is whether the Shnuggle Designs are

designs pursuant to section 213(2) CDPA at all. Are they each a design of the

shape or configuration of any part of an article?

97.

Shnuggle Design (1) is a design for the external shape

of the sides of the Shnuggle Mk 1, below a line marked “AA”, which is a

horizontal line taken from the underside of the lowest point of the rim. A

similar line marked “AA” is used to delineate what is claimed of Shnuggle Mk 2

in Shnuggle Design (3) and (4). Miss Lane submits for  Munchkin

Munchkin that the line

“AA” in both cases is arbitrary and therefore abstract, as is the horizontal

line “BB” used to delineate what is claimed of Shnuggle Mk 2 in Shnuggle Design

(5) and the oval marked around part of the base in Shnuggle Designs (4) and

(6).

that the line

“AA” in both cases is arbitrary and therefore abstract, as is the horizontal

line “BB” used to delineate what is claimed of Shnuggle Mk 2 in Shnuggle Design

(5) and the oval marked around part of the base in Shnuggle Designs (4) and

(6).

98.

She further submits that in each case, what is left is

a disembodied feature or features, which falls foul of the principles set out

in Neptune and the combination of

parts excluded is entirely arbitrary and therefore amounts to an “aspect” of a

design not a “part, contrary to the legislation and the reasoning in Neptune. Finally, she submits that even